Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain

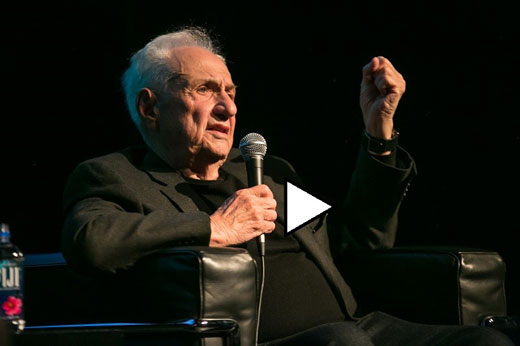

Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain Frank Gehry, after nearly six decades working as an architect, said he would like his legacy to be "transmitting feelings through materials." Gehry spoke to the Los Angeles World Affairs Council on Wednesday, March 2 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art where there is currently a retrospective exhibition of his work. Gehry said completing Walt Disney Concert Hall was a "rough one" and that when the design for the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao was first revealed his life was threatened. After celebrating his 87th birthday last weekend, he said he is spending a lot of his time on the LA River project which he describes as a "very dense problem and a very exciting prospect."

"I like to work with people I feel comfortable with and who have the same mutual interests in making environments that are humane and exciting," said Gehry who was born in Canada but says he's mostly American. When asked what he would most like to be remembered for Gehry paused, and said "I don't think about that a lot." He then told a story about a visit he made to Delphi in Greece where he saw the Charioteer of Delphi, a bronze statue from 470 BC, at the museum there. "I stood in front of it and started crying. It was so beautiful. It said artist unknown," Gehry said. "I realized that whoever made that thing way back then was able to transmit feelings through the ages to me and probably many other people who had seen it and I thought that's really what our mission is - to transmit feelings with our materials. That's the simplest description of what we do. Music is the same. Transmitting feelings with a few notes. It's very basic. So if I can do that, I'd be happy."

Gehry's most celebrated building is the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao in northern Spain, a daring titanium-clad construct that is widely recognized as one of the most important modern works of architecture in the world. Gehry said that when he was first approached to design the museum, Bilbao was in a depressed state, as the shipping and steel industries were gone and the economy was struggling. The Basque government gave Gehry a budget of 80 million euros, or $300 per square foot. "That would be about half of what it would normally cost to build a museum even then. It was very tight." He also said that when the design for Bilbao was first publicized, his life was threatened. "When I would go out in public, I would stand by the President," joked Gehry. "I figured he had body guards." Since its opening in 1997, the museum has turned Bilbao into a major tourism destination, and the amount of taxes generated by the museum for the city paid back the cost of the museum in just the first three years. To this day Gehry said the Bilbao Museum has earned the city $ 3.5 billion and now everyone in the city is welcoming to him. "I could live there for free."

More locally, one of Gehry's most recognizable buildings is the Walt Disney Concert Hall in downtown Los Angeles. "That one was a rough one," said Gehry. "I was blamed for the first go around," he explained saying "mismanagement and misunderstandings" lead to the project taking so long to build. "When I would go out to a restaurant somebody would come over and say 'how could you have done that to us?'" He said he got a lot of that and toyed with the idea of leaving town. Eventually, the team that was hired to evaluate the project exonerated him by saying nothing he did had created the issues. "The problem with projects like museums and concert halls is they have boards and they usually have people on the boards who know everything about everything," he joked. "I see it around the world. I don't know how to repair that process." He said that ultimately the architect has to be "parental and take responsibility."

When asked about his craft Gehry said, "it's not unlike any creative effort" and that includes business people, painters, and scientists. "It's all about trusting your intuition" and "being inquisitive, curious." He credits his curiosity to being embedded into his life and culture to his grandfather. He said it is important to always find new ways to do things and that this applies to everyone - from neuroscientists to people in business. "You have to invent new ways to respond to the times as they're changing - the financial markets, stress, politics... crazy politics now." On his own process he said, "I make something and then I hate it but there's something there so I try again, and then I hate that, and then I start to like it, and then everyone around me hates it, and then the good lord sends a message telling everyone to like it and they do for a while." On the projects that he spent lot of time designing but were never built, Gehry said it's "sad for me" to think about them. He said for that reason he doesn't like to visit the exhibition of his work currently at LACMA because it contains a number of unrealized plans. "When you start a project usually the economy is up," he said. "Then things happen in the world and projects slow down and stop." Gehry cited the Guggenheim in Abu Dhabi as an example saying he started it 10 years ago. "They keep saying they're starting but I'm giving up on it, it's taking so long."

Asked about why architecture is such a male dominated industry, Gehry said he teaches at architecture school and over the last 10-15 years, the schools have gradually become "at least 50% women - but you don't see them running offices. I know they're out there." He said they have senior women in their office. "We're working on it. It's a global issue and we've got to fix it. I think there are women in the industry that are equally talented and equally capable."

Discussion with Frank Gehry

When asked who his favorite architects were, he cited Erich Mendelsohn, whom he called an "unsung hero" for his urban take on modern design and how he placed together architecture from different periods. He also mentioned the Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, and the French architect Le Corbusier - Gehry said he cries when he sees his chapel. "Frank Lloyd Wright sometimes gets to me. I had the chance to meet him 3 times and I turned it down because I didn't like his politics. Now I'm sorry I didn't." And Gehry finally mentioned Rudolph Schindler: "when he was here I got to know him. I thought very highly of him."

Asked what he's going to do about the LA River, he said that first of all, "this is volunteer work." The Mayor and some friends asked him to look at it and take it on. He brought in a team of experts from all over the world - including from Holland where people have particular experience in hydrology. It is a complex project, because the river runs through 15 different cities, which involves 15 different sets of politics. "I didn't think you could just plant trees and make it pretty because it's a flood control project and a lot of water goes through it and it has serious implications - financial implications to the city." Gehry explained that there is a whole laundry list of things to take under consideration - from city planning, to education as it relates to schools along the river, as well as the health issues involved. Gehry and his team have met with many people. "We even got Jerry Brown to listen for two minutes," he said. "We're starting to study certain parts of the river - looking at structural solutions that are then design solutions which could change the character without interfering with the flood control mandate that the river has... It's a very dense problem and a very exciting prospect. I just turned 87 so I'm probably going to spend the rest of my life messing with this thing."