Marketplace's China Correspondent Rob Schmitz

Shanghai is China's biggest and most cosmopolitan city, in many ways the leading edge of change in the country of 1.3 billion people. Poor farmers come from the countryside to work on building sites and pursue their dreams, while young rich Shanghainese drive by in Ferraris on their way to visit art galleries and their slice of the Chinese dream. Shanghai is a showcase of the discrepancies between rich and poor, between China of the past and China of the future. "The economic transformation China is trying to make is historic, it has never been tried before," said Rob Schmitz, who has lived in Shanghai for the past six years. "It won't be easy, there will be some tough times over the next 10 years, but if they pull it off it will benefit all of us, Schmitz told a Global Café breakfast meeting of LAWAC on May 25th. "China has moved forward so quickly on the economic front, while political change has not - and that paradox intrigues me."

Schmitz reports from Shanghai for the radio business program Marketplace which airs on NPR affiliates. He has recently written a book Street of Eternal Happiness: Big City Dreams Along a Shanghai Road which focuses on four families that he has got to know on the street in which he lives in the city. Through their lives, struggles, hopes, frustrations and dreams he tells the bigger story of the new China, emerging from decades of poverty to become, today, the world's second largest economy. Schmitz is optimistic about the longer term future of China, which he says is full of opportunities, but he also documents the shortcomings and the enormous inequalities that have been created by China's breakneck pace of growth. "The system is not fair at all - it creates an underclass and has in some ways been compared to the apartheid system in South Africa."

He tells the story of the Zhao family, who came from a rural village to Shanghai where the mother, by dint of hard work, earns enough money to open her own flower shop on Changle St (where Schmitz lives), which supports her family. But because her family were all born in the countryside, their residence permit - the infamous "hukou" - does not give them any official rights of residence in the city of Shanghai - and when her oldest son, who is doing well in Shanghai's schools, is ready to go to high school and attempt to get into a university, he is not permitted to enroll in a Shanghai high school. He has to go back to his village of birth. He doesn't do well in the school there, flunks out and ends up working menial jobs on a golf course and in a hairdresser. "Had the hukou laws not existed in China, he would have ended up at an elite university and may have ended up in the United States." Many Chinese complain about the discriminatory hukou system, but the government isn't rushing to fix it: "You've got 300 million migrants living in the cities in China and they all have this applied to them." The government is concerned that if they granted complete freedom of movement, there would be an even greater flood of migrants into the big cities, which could lead to the creation of shanty towns and other social problems that are common in big cities in Africa and Latin America.

Another of his characters, Auntie Fu, who is in her sixties, is repeatedly fleeced by conmen running pyramid schemes that promise her enormous returns on her investments, but end up fleeing the city or going to jail before they pay out on her investments in computerized shopping machines or herbal patches to increase peoples' sex drive. Schmitz spends hours with Auntie Fu in her house trying to warn her away from such conmen, but to no avail. She, like many other Chinese of her generation, grew up poor, but now "they are surrounded by wealth, they are surrounded by these shiny skyscrapers in Shanghai and they don't quite understand how everyone made their money because they weren't taught the skills to do that." And so she stumbles into one bad investment after another, not knowing how to evaluate if they are genuine or fraudulent.

At the opposite end of the scale is a young entrepreneur, CK, in his early thirties, who sells Italian accordions and opens up a trendy sandwich shop on Changle Road. He is from a different generation, one that didn't live through the horrors of the Great Famine or the Cultural Revolution. "He didn't really know a period of stagnant growth," said Schmitz. "That generation, as they become older, I think it's going to be very interesting to see politically what happens," said Schmitz. "I do think we're going to see a pretty stark change in how they see the world, how they manage global affairs, how they manage domestic affairs. This is a generation that is incredibly comfortable with capitalism."

But CK is clearly not satistifed just making more money. "For thirty years, everyone had the same dream - the government had the same dream as the people - and that dream was to make money," said Schmitz. The younger generation has different dreams: "Those new dreams of theirs are scattering like wild fire - some of them are dreaming for equality, some dream of a value system that they feel like they didn't have growing up, or spirituality." Schmitz said China is experiencing a religious renaissance - Buddhism, Taoism and Christianity. Research estimates that there will be 250 million Christians in China by 2030. "That will outnumber Christians in any other country."

On China's leadership and the changing political situation, Schmitz said that since President Xi Jinping came into office four years ago, he has taken much more power for himself than his predecessors. "He's in charge of the military, he's in charge of the economy - he's basically in charge of everything."

The model of this faceless collective that I think was growing and reached its height with Hu Jintao start to narrow and go back to one man." Schmitz explains that he believes Xi understands that there are going to be tough years ahead - with the economy slowing down and that is a "potential problem for the party and its grasp on power and so he wants to be able to control things more personally from where he's sits." Schmitz says it would be a mistake to assume this will lead to decades of a Mao type of rule. "With China often times the pendulum will go back and forth," said Schmitz. "Right now I don't see a clear second party that could rule China." But the jury is still out on whether Xi can single-handedly manage the enormous challenges that China faces as its economy slows. And what happens when it is time for Xi to step down after his requisite 10 years at the top?

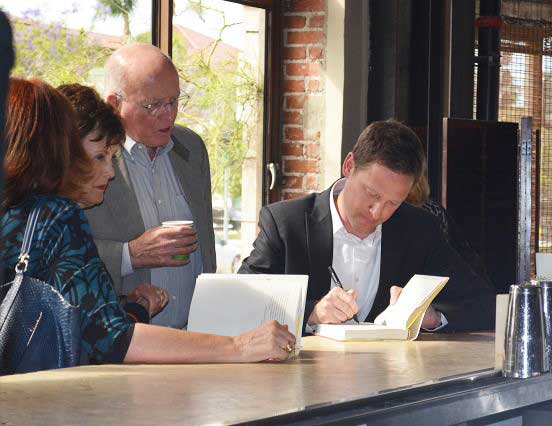

Schmitz signing his book for LAWAC members

"What I'm really interested in as a journalist is what's going to happen when it comes time for Xi to relinquish power in 2021." Schmitz said that right now Xi is surrounded by enemies because of his very unpopular anti-corruption plan, which has reached to the highest levels inside the Communist Party. "400,000 party officials have been disciplined in this campaign," said Schmitz. "That's equal to the number of elected officials in the United States." Typically China's leaders are chosen by concensus amongst the senior leaders - but if there is no concensus, the next transfer of power could be contentious.

But while the future of China's political system may be opaque, one thing is clear from Schmitz's neighbors along Changle Road - everyone in China has their dream, misplaced or not, and they are prepared to work hard for it. Schmitz discovered that the land on which his apartment is built was forcibly confiscated from a family, during which the father was killed. When Schmitz tracked down his widow, he asked her about her son - expecting to hear a tale of extended misery. But she told him that her son had gone to Cornell, earned a PhD in economics, and was now trading derivatives for an investment bank in Hong Kong. "Sometimes when you are reporting in China you hear stories that just make you stop in wonder," said Schmitz.