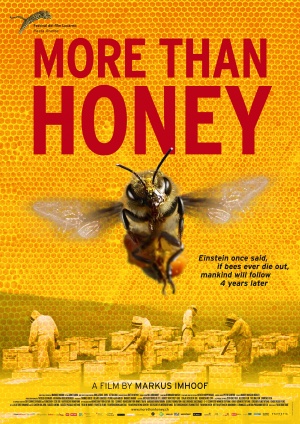

This fascinating documentary by Swiss film-maker Markus Imhoof brings the viewer not only into the world of bees and the threats to their survival, but – and this is what makes the film so memorable – it also introduces us to a range of idiosyncratic humans whose lives revolve around bees. By the end we come to realize that just as we depend on bees for honey, they depend on us for their survival.

The film starts with Imhoof explaining in a voiceover that his grand father was a beekeeper and had 150 colonies, but today bees are dying out around the world, and he wants to find out why. He opens in the Swiss Alps with an old beekeeper walking up an idyllic slope of grass and wildflowers framed by snow-capped peaks to collect a bee swarm on a tree. The man charmingly dispenses with any veils or gloves, just puffs on a short cigar as he handles the bees to keep them from stinging him – most of the time.

We then move to the almond orchards of California, where John Miller provides bees commercially to the almond producers for the pollination season, after which he loads the bee hives on trucks and brings them up to the apple orchards of Washington State and then across to North Dakota before circling back to California for the winter. This is industrial bee keeping, and it has its problems: diseases acquired in one part of the country are spread quickly by his mobile hives, and most of his bees are on a diet of anti-biotics to keep them from dying. Bees were not native to the US before the colonists arrived: they were imported to do a job.

Pesticides, fungicides, mites and other diseases and parasites have combined to put huge strain on bee populations around the world. In China Imhoof films in orchards where there are no bees left because of pesticides, and so humans buy packets of live pollen and climb up the trees and laboriously pollinate each blossom with a Q-tip dipped in the pollen. This is as far from the natural beekeeping in the Swiss Alps, as one can imagine.

The cinematography is exquisite – we see close-ups of bees mating in flight, and Imhoof uses endoscopic cameras to film inside hives as a queen bee is born and honey is made. And we learn that bees with 60,000 smell receptors can smell in stereo, and that in its 4-5 week lifespan an individual bee can make one twelfth of a teaspoon of honey.

Imhoof ends the film on an upbeat note, when he talks to a farmer in Tucson Arizona, who has found that the much-feared Africanized honey bees turn out to be not only good honey producers, but also immune to much of the disease and pesticides that are decimating the other bee populations in the US. The only problem – their sting is much stronger, and must be handled much more carefully than the way the Swiss beekeeper deals with his hives in the Alps.

The viewer is left to ponder the future of the domesticated honey bee, and what it means for our own.